In the 1960s and the early 1970s, John Lennon was a global icon, known across continents for his literate lyrics, slashing wit, rakish charm and signature teashade sunglasses. He was at once a puckish prankster and a chin-stroking philosopher — the world famous "thinking man's Beatle."

But in the last five years of his life, Lennon went into hibernation. He retreated into a domestic idyll inside the famed Dakota apartment building in New York City, devoting himself to raising his young son, Sean, and nurturing his strained marriage with his wife, Yoko Ono.

In recognition of the 40th anniversary of Lennon's assassination on Tuesday, admirers around the world are likely to revisit his Beatles heyday and his legacy as an anti-war activist. But amid those tributes, biographers and journalists say, Lennon's quiet final chapter deserves more attention.

"If he knew he was going to die, and if he was able to choose the period of his life that would be the focus in the future, it would be this period," said David Sheff, a writer who interviewed Lennon during his final months, spending three weeks with him and his family.

"He was so alive, and he felt that he had something important to say about raising his baby and marriage. That's the story he would want told, I think," said Sheff, who is also the author of "Beautiful Boy," a memoir of his son's battle with drug addiction.

In the fall of 1980, the Los Angeles Times asked Lennon to reflect on his decision to leave professional recording behind. He answered that he realized he had stopped "making records for me anymore" and had ceded too much of himself to record companies.

"Finally, Yoko said, 'You don't have to do it anymore.' I was shocked. I had never thought that: Could the world get along without another John Lennon album? Could I get along without it? I finally realized that the answer to both questions was yes."

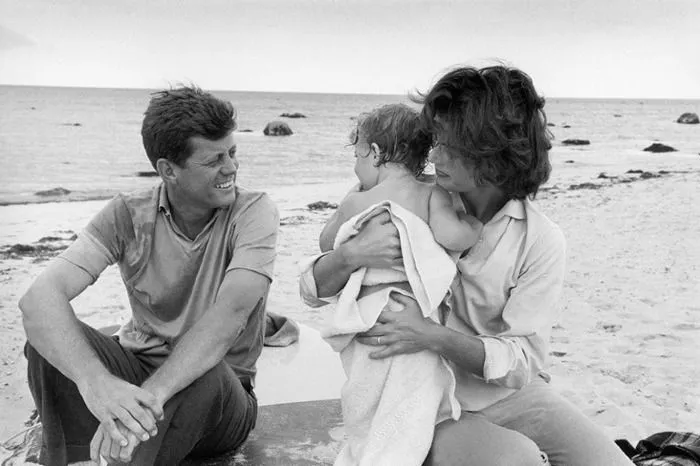

In the time from the fall of 1976 and his murder in 1980, Lennon threw himself into the simple, small-scale rituals of fatherhood. He took primary responsibility for Sean — walking him through Central Park, baking bread — and called himself a "house husband." Ono, meanwhile, managed the family's sprawling business portfolio.

"He was probably, in those years, the most notable stay-at-home dad in America," said Larry Kane, author of "Lennon Revealed," a 2005 biography, and "Ticket to Ride," a chronicle of the Beatles' early American tours.

It was a pointed turn for a celebrity who was once one of the international avatars of the "sex, drugs and rock-'n'-roll" cliché. Lennon said he bottomed out while he was separated from Ono in the early 1970s, during an 18-month "long weekend" of substance abuse, according to Kane.

But it was also an unusual role for a middle-age man in that period: Just 2 percent of American households had stay-at-home fathers from 1976 to 1979, according to a Pew Research article citing a 2013 study published in the Journal of Family Issues.

Lennon, according to news articles published at the time, apparently had some help from a nanny. But nearly all contemporaneous stories depict Lennon as a steadfast and joyful father, totally consumed with domestic life. ("Lennon Is Playing Daddy," a headline from the time read in part.)

"John talked baby talk, tickled [Sean], threw him in the air, slipped him between his knees and prompted him with spontaneous learning games. ... There was no mistaking it: John was Sean's mommy," Sheff wrote.

But, as students of Lennon's life readily acknowledge, he was far from the perfect father or husband. He was — by his own admission — physically and verbally abusive to his first wife, Cynthia Powell, who died in 2015, and he was often cold and distant with their son, Julian.

Julian Lennon, who declined an interview request, has spoken candidly about his troubled relationship with his famous dad, who also had an absent father.

"I have to say that, from my point of view, I felt he was a hypocrite," Julian Lennon told The Daily Telegraph in 1998.

"Dad could talk about peace and love out loud to the world, but he could never show it to the people who supposedly meant the most to him: his wife and son. How can you talk about peace and love and have a family in bits and pieces — no communication, adultery, divorce? You can't do it, not if you're being true and honest with yourself."

Beatles aficionados are likely to be familiar with the emotional chasm between father and son. Paul McCartney reportedly wrote "Hey Jude" — a ballad originally known as "Hey Jules" — to cheer up Julian, who was despondent after his father left his mother.

And yet, in the final years of his life, Lennon appeared to become keenly self-aware and self-critical. He seemed to recognize that he could find redemption by committing himself to his second wife and second son, referring to the period as a "penance" for the sins of his past.

"He offered a brutally self-critical assessment of who he had been as a man," Sheff said, referring to their conversations. "I think he was trying to make amends for the person he had been."

Lennon's final months also marked the start of what could have amounted to a new artistic chapter. In August 1980, Lennon and Ono began recording their fifth album, "Double Fantasy," a sentimental celebration of home and hearth shaped by Lennon's low-key domestic years.

The 14-track record, which was released that November, opens with the thematically apt "(Just Like) Starting Over" and arguably reaches its emotional climax with "Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy)," a track written for Sean.

"In a way, we're involved in a kind of experiment," Lennon told The New York Times in an article published Nov. 9, 1980. "Could the family be the inspiration for art, instead of drinking or drugs or whatever? I'm interested in finding that out."